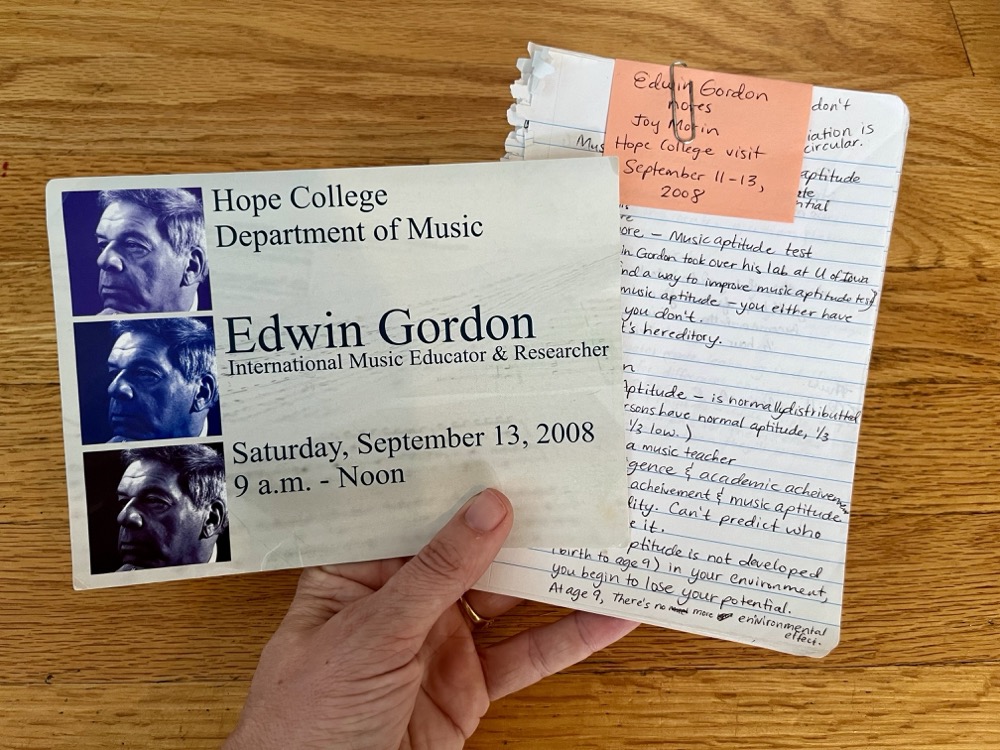

It was September of 2008, and I was an undergraduate college student at Hope College (Holland, Michigan) at the beginning of my senior year as a piano performance major.

One day, the professor of one of my classes announced that a guest by the name of Dr. Edwin E. Gordon would be visiting campus for a few days. Dr. Gordon was to deliver a lecture, lead a Saturday workshop, and join our class to tell us about his research and theories regarding music learning.

As our preparation, my professor assigned readings from two of his books, Learning Sequences in Music: A Contemporary Music Learning Theory and Music Learning Theory for Newborn and Young Children. I found myself unaccustomed to Gordon’s style of academic writing and unable to fully grasp the meaning of what he wrote. However, I did my best to understand to become familiar with a bit of his work before he arrived. I could tell my professor was looking forward to having us hear from Dr. Gordon.

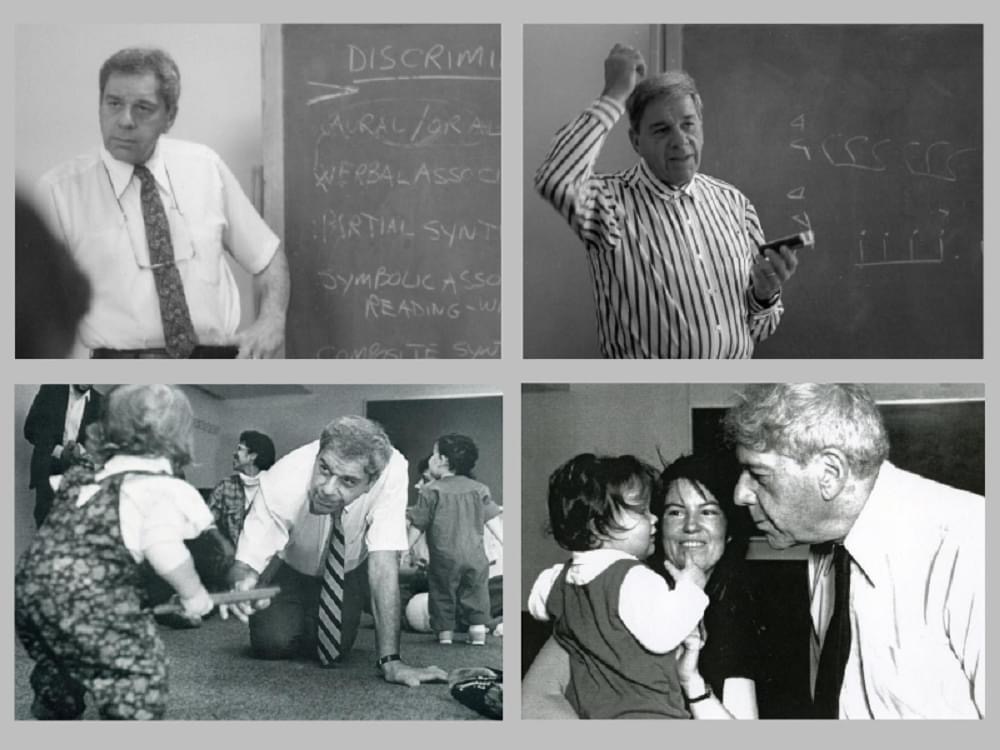

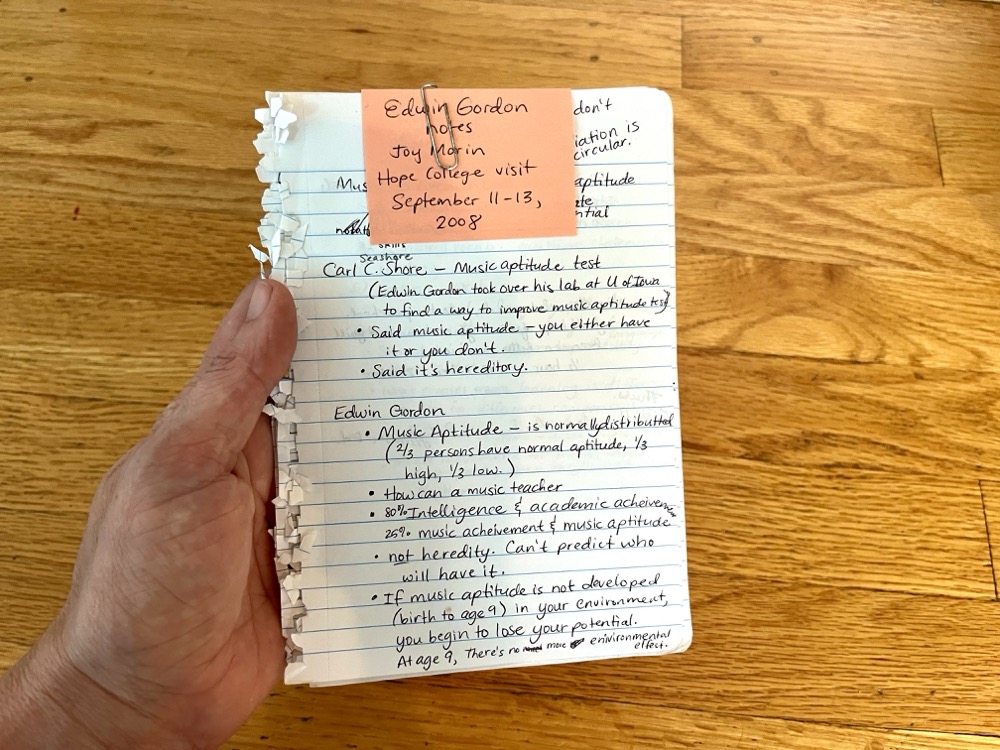

Dr. Gordon seemed totally relaxed as he sat with us around a big table during class. He talked off-the-cuff about his early career developing music aptitude tests in continuation of the work of Carl E. Seashore at University of Iowa. He discussed the difference between music aptitude (our potential) and music achievement (what we’ve learned), and how the research suggests music aptitude can increase (or decrease) during early childhood — thanks to the richness of one’s music environment — until stabilizing around age 9. He stated that due to that variability of developmental aptitude, teaching preschool children was the most important work we can do as music educators. He also talked about “audiation” — a mysterious term that meant music comprehension or the process of “thinking in music.”

[Related article: What is Audiation, Exactly?]

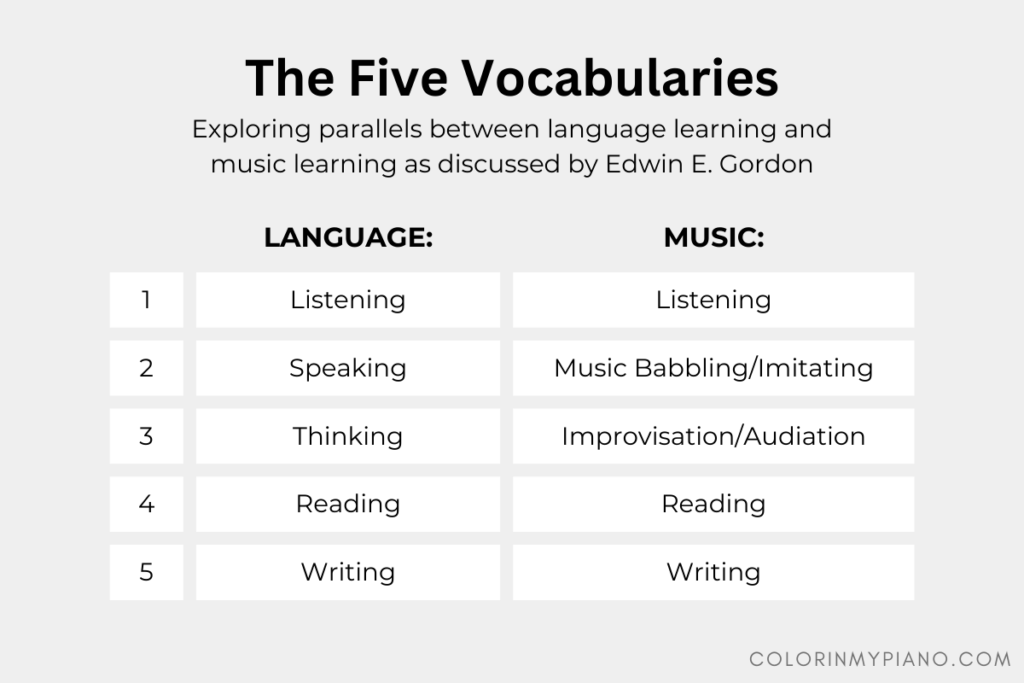

Gordon went on to define a rich music environment as one that nurtures five vocabularies, similar to those of language learning. First, we develop a listening vocabulary. This is when we hear and listen to music in our environment. Second, we start “talking” or music babbling, developing our speaking vocabulary. Third is our thinking vocabulary — allowing us to think and use music on-the-spot, just as we can spontaneously speak in language. Fourth is the reading vocabulary and fifth is the writing vocabulary — which develop only after we have experience with the first three vocabularies.

Gordon considered this language analogy extremely useful for understanding how our minds and bodies naturally learn and understand music.

After witnessing Gordon’s informal chat with us during that Thursday class, I decided I absolutely had to attend the workshop for music educators he would be giving on Saturday. I had to hear more about his research and ideas on how music is learned.

What follows is a paraphrase of my handwritten notes from attending Gordon’s workshop that weekend. Gordon began the workshop by elaborating more fully on the five vocabularies and the many parallels between the processes of language learning and music learning. Along the way, he touched on a variety of interesting insights and recommendations for teaching.

1: The Listening Vocabulary

Gordon stated that the first vocabulary, the listening vocabulary, is missing in most music programs. To increase your vocabulary, you need to listen to a great variety of music. Repetition is the death of learning. We learn most from differences, not sameness.

To that end, Gordon recommended singing lots of short songs without words (using a neutral syllable like BAH) to children. Sing in Major, and then follow it with something different. Expose them to Minor, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, and Locrian. As a first skill, teach them to sing the resting tone. Singing in tune comes from being able to always hear the resting tone.

As for the rhythm side of things, Gordon recommended chanting short rhythm chants (like songs, but consisting of spoken rhythm). Have a rhythm conversation with students. Let them hear Duple meter versus Triple meter. Then, go to 5s and 7s. Get students to move. The more movement, the better. In music, we tend to try to teach time before space, but movement in space is actually the foundation for learning time.

2: The Singing Vocabulary

To develop the singing vocabulary, Gordon suggested students shouldn’t learn the musical alphabet right off the bat. Instead, learn tonal patterns and rhythm patterns. Always establish tonality and/or meter, to help nurture audiation and thereby avoid mindless imitation and memorization.

Gordon demonstrated how to have students echo tonal patterns and rhythm patterns. He recommended using solfege; specifically, moveable DO with LA-based minor. Some teachers think solfege teaches hearing; but actually, hearing teaches solfege.

For rhythm, Gordon recommended using a rhythm syllable system that is based on beat functions — meaning, related to the macrobeats and microbeats that are establishing the meter. You need to be audiating macrobeats and microbeats in order to understand rhythm, just as you need to be audiating the resting tone in order to understand the tonal aspects of music. He then demonstrated the Gordon-Froseth rhythm syllables.

Once children show they can find a resting tone and find macrobeats, they are ready to learn an instrument.

In conventional music education, we tend to teach the Laban effort factors in the order of time, space, weight, and flow — but research shows children learn exactly backwards from that.

Regarding piano teachers, Gordon queried: why does one need a license to cut hair, but not teach piano? By this, he meant to challenge conventional piano teaching for tending to teach students to merely “See this, do this,” without student comprehension. [Gordon certainly didn’t sugarcoat what he thought!!]

3: The Thinking Vocabulary

Building on the listening vocabulary and a speaking vocabulary, we next gain a thinking vocabulary — improvisation. Just as we can learn to spontaneously think and communicate through language, we can learn to improvise with music.

Gordon said to teach improvisation before notation. It gives notation more meaning. Establish the sounds first. Just like with language, we ideally learn how to “think” in music before reading and writing in it.

This involves learning to hear differences (thanks to the speaking vocabulary) between tonal patterns, calling them tonic and dominant patterns, for example; and differences between rhythm patterns, calling them macro/microbeat patterns versus division patterns, for example. It involves having students vocally improvise patterns in response that are different from yours. After teaching melodic and rhythm improvisation, teach students to vocally improvise in chord progressions.

Gordon explained that the reason 90% of professional musicians can’t improvise is because they have not developed their singing or thinking vocabularies.

Gordon encouraged: Don’t try to clone someone’s teaching style; just learn how children learn sequentially, incorporate many methods into your teaching style, and then you’ll be effective.

Likewise, don’t get hung up on teaching methods. There are many ways to teach. Just know how children learn, and there’s no wrong way to teach.

Notation is highly overrated. The most important things can’t be put into notation, like musicality, flow, etc.. Originally, notation wasn’t first; audiation was.

Gordon encouraged: Improvise more. It will make you a better reader.

4: The Reading Vocabulary

The fourth vocabulary is the reading vocabulary, which is essentially: can you hear what you see?

Forget about key signatures; just know where DO is. You don’t have to know letter names in order to read.

When it comes to rhythm reading, Gordon pointed out that rhythm by nature is “enrhythmic” — meaning, any given rhythm pattern can be notated multiple ways. (Just as two “enharmonic” tones sound the same but can be notated different ways, “enrhythmic” rhythm patterns sound the same and can be notated in different ways.)

For example, anything in a time signature of 3/4 can be notated enrhythmically in 6/8 time, with each two measures of 3/4 put into a single measure of 6/8. The same is true in various Duple Meters: things can be notated in 4/4, 2/4, 2/2, etc. Gordon even went as far as to state that all we need is 3/8, 4/8, 5/8, and 7/8, and you can teach every song ever known to mankind. Everything else is enrhythmic.

5: The Writing Vocabulary

The fifth vocabulary, the writing vocabulary, is closely related to the reading vocabulary. Gordon basically stated that it is simply a matter of learning to write what you hear. When you’ve start with the listening vocabulary in the beginning, learning to read and write is not difficult.

As the workshop time came to an end, Gordon discussed the distinction between music aptitude (potential) and music achievement (what one has learned). He posited that when most teachers see achievement, they tend to assume it’s aptitude. But there’s a lot of unrecognized aptitude. So much music aptitude is wasted. (Of course, we never use our full potential anyway; Einstein used 19% and the average human uses around 12%).

Most teachers teach as if everyone in the classroom is average. Gordon believed in individualizing instruction accordingly for high, average, and low music aptitude students. He suggested teachers administer a music aptitude test (such as his PMMA, IMMA, MAP, or AMMA) so they can give each student in the classroom what they need in terms of easy, moderate, and difficult rhythm patterns and tonal patterns.

Gordon’s parting words during the workshop stressed the importance of teaching early childhood music. Gordon considered teaching that age group to one of the most important things we can do to pass music onto the next generation.

Over the years, I’ve occasionally pulled out my notes from this first encounter with Gordon and his Music Learning Theory (MLT) in 2008. Those handwritten pages bring me a lot of joy as I remember how I felt as an undergraduate music major, hearing Gordon speak at that point in my life. I knew after hearing him speak I wanted to learn more about MLT in the future and applying it to my teaching practice.

Thanks to that chance encounter, Gordon’s work continues to be an influence on my teaching philosophy and practice. Off-and-on over the years, I’ve attended professional development offered by the Gordon Institute for Music Learning, engaged in self-study of Gordon’s writings, and experimented with ways to apply MLT with my piano students.

MLT isn’t something you can learn and apply overnight. You can easily spend your entire lifetime studying to understand how we learn music, and never learn it all. And that’s one of the things I really like about MLT! Hearing Gordon speak was enough to whet my appetite for a lifetime of learning and experimenting in my teaching.

If you’d like to take a peek at my handwritten notes for yourself, you can CLICK HERE to view a PDF scan.

Keep in mind that my notes do not represent Gordon’s lifework or even his talk that weekend comprehensively or completely accurately. However, I hope you’ll find them, as I do, interesting for what they are: a reflection of who I was as a young person hearing Gordon’s ideas for the first time as I interpreted his talk at Hope College that lucky weekend in September of 2008.

Thanks for traveling time with me to my college days to remember this experience. I hope you are as impacted by Gordon’s message as I am.

Your turn: What struck you most from Gordon’s message? I would love to hear. I’ll share my own favorite lines in the comments below!

Related:

- What is “Music Learning Theory”, Exactly?

- What is Audiation, Exactly?

- YouTube: Music as a Language by Victor Wooten – A discussion of the similarities between learning language and learning music.

- Recommended Reading From Edwin E. Gordon’s Books on Music Learning Theory (MLT)

- 2024 Piano Level 2 Certification through the Gordon Institute for Music Learning – A peek into what taking a Professional Development Levels Course certification through GIML is like.

- Join the Facebook group, “Edwin E. Gordon and Music Learning Theory for Piano Teachers.” All welcome! Visit the group here and click the “Join Group” button to request to join the group.

Here’s some of my favorite lines from my notes. (Please remember: these are not direct Gordon quotes; these are my notes taken during his workshop.)

– Music is not a language, but we learn music the same way we learn language.

– We learn from differences. Repetition is the death of learning.

– Some teachers think solfege teaches hearing. But hearing teaches solfege.

– Time-space-weight-flow is how we tend to teach the Laban ideas – but research shows children learn exactly backwards from that.

– Don’t try to copy someone’s teaching style. Just learn how children learn sequentially and incorporate many methods into your teaching style, and then you’ll be effective.

– Don’t get hung up on teaching methods. There’s all different ways to teach. Just know how children learn. There’s no wrong way to teach.

– The most important things can’t be put into notation. Musicality, flow, etc. Notation is highly overrated. Originally, notation wasn’t first — audiation was.

– Just use 3/8, 4/8, 5/8, and 7/8 and you can teach every song ever known to mankind. Everything else is enrhythmic.

– Teaching early childhood music is one of the most important things you can do.

[email protected]

Caren Worel

I remember watching videos of you with your daughter at the piano.

Are you using these ideas with them?

I feel kind of guilty for not teaching that way.

I did not have a Music degree. I have a Child Development and teaching degree. I started piano at age 6, and had lessons throughout highschool.

I taught (at first) the way my teachers taught me.

I was a terrific sight reader…. emphasis on teaching reading.

I keep learning and incorporating new things.

Gordon makes a huge amount of sense.

I’m 77 and may have missed the boat. ?

Thanks for sharing the notes!!!

Hello, Caren! Yes, I’m still using an MLT-based approach with my daughters. I love the idea of developing their ears and bodies for music in an “immersion” way, just like learning a first language, and it’s been fun to see them respond to it!!

It’s very different from the way I was taught, just as you indicated for yourself. Like you, I was a strong sight-reader early on. I think we all tend to teach the way we were taught, and the conventional way of piano teaching with a heavy emphasis on reading is common and widespread — for better or for worse. Gordon makes a lot of sense to me, too. You’ve not missed any boats. 🙂 I say it’s NEVER too late to incorporate whatever ideas are attractive to you as a teacher. As you said, it’s fun to keep learning and incorporate new things!!

Thanks for sharing your experience and perspective, Caren!

THANK YOU, Joy for writing up this detailed and concise summary of MLT as you saw it for the first time. And you are correct in saying it is NEVER too late to keep learning about teaching. I will never forget the visit you and Amy made to my studio. – Nancy

Thank you, Nancy! I well remember Amy’s and my visit — it was so kind of you to open up your home studio to us. I hope all is well with you!!