In today’s post, please enjoy an interesting and insightful interview with pianist and teacher Chad Twedt (pronounced “tweed”). I’ve known Chad for a number years, having connected online thanks to blogging. Chad’s blog, Cerebroom, is where he posts occasional in-depth articles about topics relating to music and more. Below, I ask him to share about his recently released online course called The Art of Rubato, his teaching philosophy, and his compositions, among other things.

Hi, Chad! Thanks so much for agreeing to this interview. Would you begin by telling us a little bit about you and how you got into teaching?

Thanks Joy, I’m honored!

I have a master’s degree in piano performance and a bachelor’s degree in mathematics. I love composing, performing, teaching, thinking/researching, watching movies, writing, coding, and playing tennis.

In high school, people used to ask me the dreaded question that almost no high schooler can answer: “What do you think you’ll be doing 10 years from now?” I used to answer, “I don’t know… the only thing I know for sure is that I’m not going to be a teacher.” I said this because the only people I saw teaching were public school teachers who, in my view, had a difficult job – sometimes horrifically difficult, dealing with kids in every class who didn’t really want to be there. I also hadn’t met any male private piano teachers. Becoming a piano teacher wasn’t even on my radar.

I started teaching in 1997 reluctantly when a 10-year-old kid who sat in the front row in my undergraduate junior recital begged to take lessons from me. I told his parents that I was a performer, not a teacher. He apparently really wanted to study with me, because they called me back the next day and pleaded with me again to give it a try. I agreed, and I was nervous I’d run out of things to say after the first 10 minutes. The opposite happened – I felt like each 30-minute lesson was way too short. Unfortunately, the kid never practiced. His parents later told me he idolized me and just wanted to be around me, so he only lasted a month as a student, but it was enough for me to realize that teaching piano was something I was good at and deeply interested in. I felt I owed it to myself to explore it some more. Fast forward 20+ years, and here I am!

As a piano teacher, what are your goals for your students?

In each lesson, I am obsessively focused on preparing students to practice effectively at home. This obsession increased tenfold after I did a ton of research into metacognition, which is the idea of “thinking about thinking.” It is what allows students to plan a practice/study strategy, monitor that strategy, and evaluate the success of that strategy, rather than just mindlessly seeking pleasure, producing minimal results. Students of all ages, especially adults, naturally exhibit metacognitive knowledge and skill when they study for academic tests, but they tend to be far less mindful when practicing piano.

I also strive to make sure that my students are comfortable performing for others from memory. I think this is one of my biggest strengths as a teacher. To some teachers this might sound like a pretty standard teaching goal to have, but over the past decade or so, the trend has been to push more and more for emphasis on sight-reading rather than memorization. This is a subject that I’ve looked into a lot, both in terms of psychology as well as benefits/drawbacks of memorization-oriented learning vs. sight-reading learning in my preparation threshold and memorization vs sight-reading articles (not to mention the practical side of it which I discuss here). The pedagogical arguments I’ve seen in articles, presentations and forum discussions advocating for more emphasis on sight-reading and less emphasis on memorization are not convincing to me.

What is unique about your teaching approach?

Probably most unique is my obsession in getting students to understand the “why” behind everything I’m having them do, down to the smallest detail. Why put a dynamic peak in this or that spot? Why choose one articulation pattern over another in some piece of Bach? Why is one fingering objectively better than another? Why put rubato here or there? Why float the wrists between phrases? Why, why, why? I know that some students are emotionally content to just carry out orders without knowing why, but emotional satisfaction and intellectual preparedness are two different things. Even students who are content to “play without understanding” will remember what they’re doing better when the “why” is generously shared with them, not to mention this knowledge will transfer far more effectively to pieces they learn in the future when they learn the “why” behind everything they do.

As a student, I wasn’t disrespectful, but it really bothered me internally if I was ever asked to do something without knowing why… or even worse, when I was asked to do something that went against my internal senses. Trying to get myself to follow instructions I didn’t fully understand felt to me like trying to run fast in one of those nightmares that takes place in slow motion. Try as I might, my mind and body fight me. I feel this obsession with “why” has been advantageous in teaching, because I know it causes me to break things down more than most do.

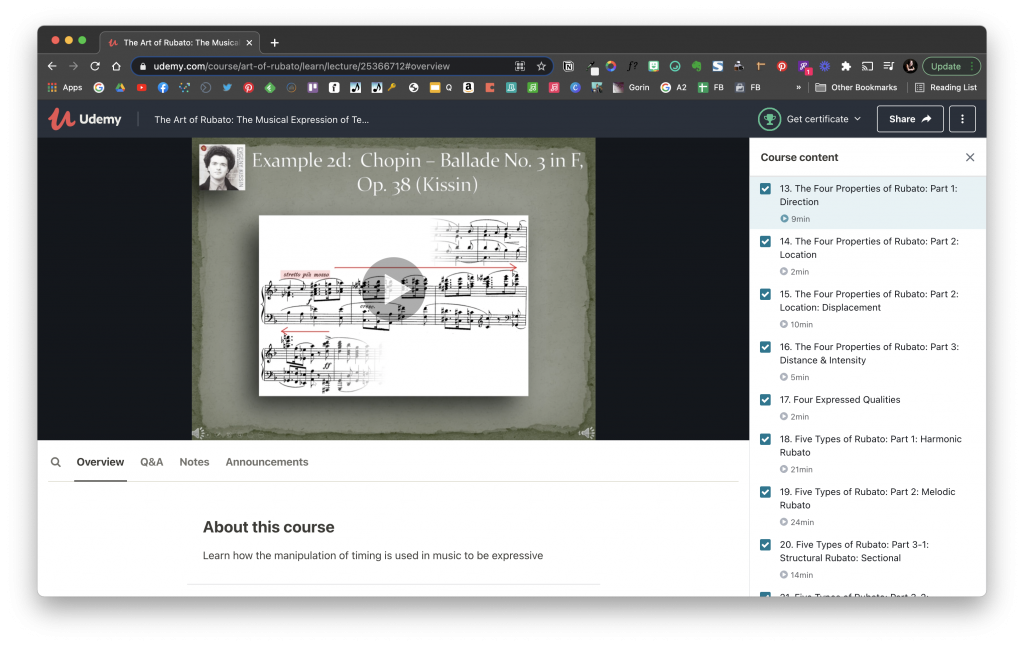

You recently released your first online course, called The Art of Rubato. Could you tell us about it?

Yes! It is a six-hour video course that I published on Udemy, and it’s the only course in the world that exclusively teaches rubato at all, let alone in an organized, fully comprehensive manner. In the course I identify four properties of rubato, four general purposes of rubato, five types (with many sub-types) of rubato, and three types of compound rubato. I use over 140 audio excerpts of polished performances of standard repertoire – everything from intermediate to virtuoso repertoire, covering all eras of music from Bach to Barber. I designed the course to be useful for any musician, from the intermediate piano student to the college music professor. It’s also a course that any musician can take, not just pianists. Rubato is rubato, no matter what instrument is performing it.

What led to your desire to delve into the art of rubato?

Early in my teaching career when my first students started advancing to a level where rubato became more relevant, I became deeply frustrated by how little I explicitly understood about rubato. I did some digging and was disappointed by what little I found in books and articles. It was clear to me that even the experts were just winging it when they talked about rubato. Everyone had their tips, tricks and bits of understanding about rubato that all made sense, but I couldn’t find any comprehensive framework that could be used to teach rubato to students (or to just wield as a performer).

Much like what I did with the Matrix movies and my crazy Matrix ReSolutions website (one of my contributions to humanity), this became a puzzle that I just had to solve. I already listened to the 1200 piano CDs in my music collection all the time, but at that point I started listening specifically for rubato. After a couple years of obsessing about it, I had formulated a system of analyzing, notating and teaching rubato that I started using with my students.

I thought that surely I couldn’t possibly be the first person over the course of the past couple hundred years to do what I had done. I finally broke down and purchased a $100, 450-page textbook on the history of rubato called Stolen Time by Richard Hudson that I had been eyeballing for a while. According to Hudson, some had tried but failed to develop a system of detailing the various properties, purposes, behaviors, etc. of rubato. One pedagogue concluded it’s too personal for any “system” to be developed. Having accomplished exactly this, I didn’t know whether to feel proud or confused! Maybe a little of both!

How is your course useful to pianists and piano teachers?

The course presents a system of analyzing, notating and teaching rubato that eludes us until we see it, after which it seems very intuitive and natural. After taking the course, performers and teachers will feel extremely confident as they know why they use all the rubato they use. It does not give them any kind of “formula” to “calculate” where to put rubato. But it does give them a set of concepts, rules and guidelines (just like we have in traditional music theory and performance practice) so that they know “how to think” in the realm of rubato. If you don’t have concrete, well-defined vocabulary and concepts to describe the various aspects of a musical phenomenon, then that phenomenon will forever remain in the realm of musical spiritualism and mystery rather than being assimilated into the realm of science and pedagogy.

Many teachers have told me that learning about rubato changed the way they hear music. One teacher went to a symphony performance a while after hearing my presentation, and they told me that they found themselves listening to all of the music through this new “rubato lens” during the whole concert, calling the experience “enlightening.”

To quote myself from the course: “Rubato that is felt is expressive, but rubato that is both felt and understood is more expressive.”

What was it like to create and publish your own video course through Udemy?

It was a lot more work than I thought it would be! The audio editing and photoshopping sheet music excerpts alone was a solid month of work. Writing the script, creating the visuals, and then actually recording it and getting it right were all a huge undertaking. But in the end, it was worth it. I produced a high-quality course, not only in terms of the content but also in terms of presentation.

As for Udemy itself, I feel like Udemy does a great job trying to give instructors what they truly deserve as compensation for their work. Udemy is run the way I’d probably want to run an online education business if I were to run one myself. If someone buys my course by searching on Udemy, I keep 50%. If someone buys my course through a link I provide, I keep 97%. The 3% Udemy is making on that still works out to be a lot when you have 35 million users, so this business model is a win-win for everyone. Clearly Udemy is not out to exploit those who provide content on their site.

In addition to performing and teaching, you are also a composer! Would you tell us about the compositions and other resources you offer on your blog?

Sure! My most recent composition was actually a commission from a very talented four-piano ensemble group called Piano 4te. The piece is called Cosmosis, and you can hear it here, although the recording might be barely tolerable to some since it’s just a computer rendering from my music notation software.

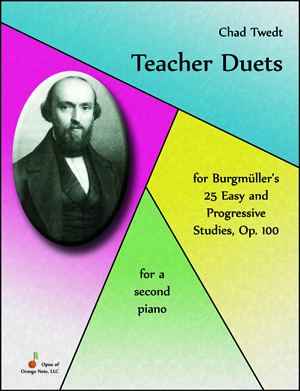

Before that, I published Teacher Duets for Burgmuller’s 25 Easy and Progressive Studies, Op. 100 for a second piano, and that has been a popular item among teachers as it makes the Burgmüller pieces (a staple of our teaching repertoire) sound like sophisticated pieces of music for the concert stage.

I also very recently published two Dragon Suites for solo piano (here and here), which are concert piano arrangements of video game music by Jordan Steven, similar to what has been done with the Final Fantasy video game soundtracks. After I was asked to write the arrangements, I decided it would be a super interesting and exciting project since the original music is so far removed from typical piano music. I think the pieces would be a super interesting contrast in a program full of Bach, Beethoven and Chopin.

My earliest compositions are the works from my Ostinato album: Ostinato Suite No. 1, Ostinato Suite No. 2, 9/11 Portrait, and Life of a Rain Cloud. You can hear audio samples of each of these on these pages.

Those who are interested in absurd arrangements might also be interested in my piece “Solfeggissimo.” It is hardissimo to play.

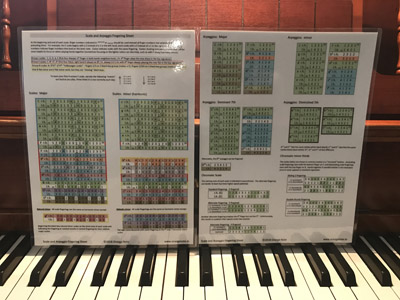

I also offer a scale and arpeggio fingering card, which is a laminated, double-sided, 8.5×11 sheet that gives students fingerings of all 12 major scales and all 36 minor scales, all 24 major/minor arpeggios, dominant/diminished 7th arpeggios, several fingerings for the chromatic scale, and even chromatic thirds. I grew tired of writing scale/arpeggio fingerings into students’ notebooks, and I believe scale/arpeggio “books” are a waste of money when I already give my students the theory background to figure out the notes of the scales I assign to them. I also believe the scales are learned more quickly and retained more effectively when students figure out scales on their own. Laminating of course isn’t cheap, so packs of 5 cards go for $20, but I’d rather have students get a $4 card with everything they need right there that will last their entire lives (and doubles as a handy sheet music bookmark) than have them buy a $10 book.

All of my stuff can be found at orangenote.site.

Do you have any other current projects?

Yes, in fact the majority of my “project time” over the past seven years has gone into the designing of MetaPractice, an app that will help teachers teach and help students practice based on a ton of research I did into metacognition. I don’t want to say much about it at this point since it’s currently in private alpha testing while coders add the last remaining features, but I’ve been using it very successfully with my own kids for a couple months, and I’m extremely excited about its release. It is designed for goal-oriented teachers who want their students to be goal-oriented when practicing.

At this very moment, now that I’ve completed my rubato video course (and while I wait for the coding of MetaPractice to be completed), I’m collaborating with the creator of mynoise.net to make a piano “soundscape,” which is fun as it involves a very different kind of musical writing, much more challenging than it would seem.

How can teachers learn more about your music, resources, and online course?

Anything of significance that I do in the future will be announced on my blog, Cerebroom, so that’s probably the best way to follow what’s going on. Updates don’t go out very often (just when I have something very important to say), so Cerebroom subscriptions won’t flood anyone’s email boxes. At my Udemy rubato course, there is a promotional video there as well as real sample videos from the course.

What else would you like us to know?

I’m the events coordinator for a local tennis club, running several different tennis events for men and women. I can also create a large cavity between my hands and blow into a slit made by my thumbs to make the sound of a mourning dove.

Thanks so much for chatting with us, Chad! It was great to hear about your new rubato course as well as your compositions and other projects!

Hello again, readers: Just wanted to tell you I completed Chad’s rubato course recently and I must echo what other teachers have said about it: I hear rubato in an all-new way and I’m pleased to have a more effective way to teach rubato to my students. I’d recommend The Art of Rubato course to any teacher interested in helping their intermediate and advancing students use rubato in a more deliberate and well-grounded manner in their playing. Check out this link to learn more!

Hope you enjoyed reading this Teacher Feature!

Links:

- Chad’s The Art of Rubato course

- Chad’s music blog: Cerebroom

- Chad’s Matrix ReSolutions website

- Chad’s Piano Studio website

- Chad’s professional artist website

- Chad’s general blog, Read Twedt

- A Facebook video of Chad performing

I really enjoyed this interview. I want to check out all the links too.

Glad you enjoyed it, Caren!

I would be interested to know if Chad found it difficult, being a mathematician, to add Rubato to his playing? Whether his brain rebelled at the thought of not sticking to the exact rhythm as written of a piece?

Myself, having learned to improvise from the beginning of my lessons and learning in a playing-based environment, has made Rubato a natural part of my playing.

Hi Leeanne, Chad here! Being good at math is not a handicap in experiencing the emotional side of music, and in fact research seems to show over and over again that there is a strong correlation between aptitudes in music and math. My strongest music students are typically also good at math, and I’m not just talking about the ones who are good at getting the right notes and counting; I’m talking about the ones who can handle the rubato in a Chopin Mazurka.

So no, my brain didn’t rebel at the thought of adding rubato. In fact, starting in 8th grade, I started buying CDs like crazy, getting 12 CDs for the price of 1 through BMG and Columbiahouse over and over again. I built a collection of piano music that is now 1200 CDs, and I listened to it for hours every day while doing homework. Consequently, rubato was a natural part of my playing for me as well. Sometimes I did it with little or no deliberate thought. That’s fine for performing, but in the context of teaching, that is not a virtue, nor is it a quality of teaching that is unique to any teacher. All teachers, even non-teaching performers, can teach with the “here’s how I do it, now you try it” method.

But I do believe that someone who is not conditioned to rubato would of course think that rubato sounds strange when they first hear it. My course is geared toward both audiences, but it is geared MUCH more toward people like you who are comfortable with rubato. It’s like the piano student who learns music theory via experience but doesn’t formally study music theory until college. I’ve known a few musicians who were trained that way. In that scenario, light bulbs goes off left and right when they finally study theory and they put “names” to things they’ve done before. For most, that is an exciting, eye-opening experience. Some of them even resent their K-12 teachers for not teaching them theory, while others are OK with it, but what they all have in common is that they pick up the terminology very, very quickly because they already have experience dealing with it. That’s how I think my course will be experienced for people who are comfortable with rubato. And I absolutely know it will open additional doors of creativity for how to think about, experiment with, and teach rubato, for everyone who takes the course, including college professors who have lived and breathed rubato their entire teaching lives.