[Click here to go back to Day 1.]

I’m so excited to share with you highlights from the recent 2019 Music Teachers National Association (MTNA) national conference!

Pedagogy Saturday is an optional day of the conference, comprised of a variety of “tracks”: Advanced Piano/Teaching Artistry, Entrepreneurism, Musician Wellness, Recreational Music Making, and Teaching Students With Special Needs. It’s not easy to decide which sessions to attend, but I ended up choosing the Advanced Piano/Teaching Artistry track for most of the day, and then I switched to the Recreational Music Making track in the afternoon.

8:00am The Secret Lives of Phrases: Lies, Near Lies and Red Herrings, by Deborah Rambo Sinn

Deborah Rambo Sinn gave an interesting session about deconstructing phrases in order to build lyricism. She shared interesting examples from the piano literature where the phrase markings are confusing or deceiving.

So often, we find phrases marked in a way that does not reflect the way the phrase seems to go. Why do composers write slur markings that end before the phrase actually ends? Sometimes, it because the composers are making sure we don’t break a phrase in a particular place. Today’s composers are doing a much better job than composers of the past in marking phrases the way they want them played.

In her teaching and in her own study, Deborah finds it useful to find and mark the phrases, sub-phrases, and sub-sub-phrases in a melody. In this work, there are no right answers. Instead, it’s a matter of finding an answer that works.

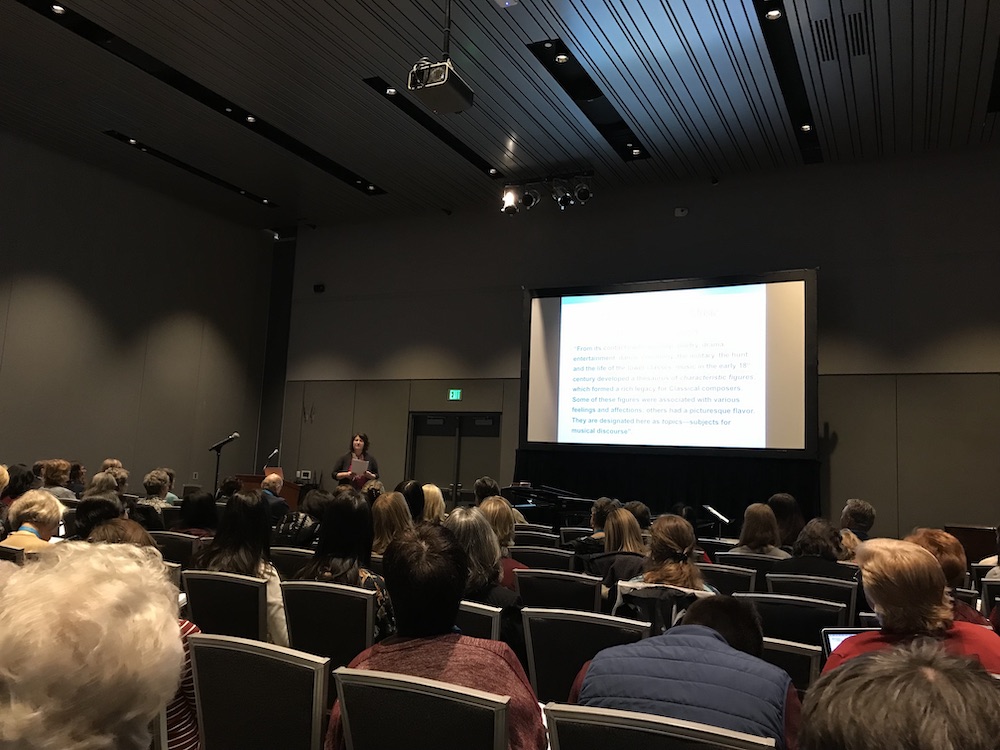

9:15 The Art of Interpreting Keyboard Music from the Classical Period, by Kay Zavislak

Kay Zavislak gave a fascinating presentation, based on the work of musicologist Leonard Ratner, about the art of interpreting keyboard music from the classical period.

The most important thing in music performance is understanding and portraying the underlying character and personality of the piece. However, in Classical era works, titles such as “sonata” or “sonatina” are often used — letting us know it is an instrumental piece as opposed to a vocal piece, but providing little indication of the character and personality of the piece.

A solution to this problem is to pay attention to the style being implied by the composer’s notational markings for the piece.

In the 1980s, musicologist Leonard Ratner’s presented his “topics” theory: “From its contacts with worship, poetry, drama, entertainment, dance ceremony, the military, the hunt, and the life of the lower classes, music in the early 18th century developed a thesaurus of characteristic figures, which formed a rich legacy for Class. Some of these figures were associated with various feelings and affections; others had a picturesque flavor. They are designed here as topics–subjects for musical discourse.”

Here is an overview of Ratner’s “topics” for Classical period music:

| A. Dance types: | B. Styles: |

| 1. Minuet 2. Sarabande 3. Ländler 4. Polonaise 5. Bourrée 6. Contredanse 7. Gavotte 8. Siciliano 9. March/Entrée/Intrada | 1. Military and Hunt Music 2. The Singing Style 3. The Brilliant Style 4. French Overture 5. Musette/Pastoral 6. Turkish March 7. Storm and Stress 8. Sensibility/Empfindsamkeit 9. The Strict Style/The Learned Style 10. Fantasia |

[Note: Curious to know where to learn more about Ratner’s topics, I did some Googling and found his book available on Amazon here as well as the the most recent Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory here. Both books look interesting.]

Kay then conducted a listening game, where she played excerpts of classical period music with the audience guessing which topic they were hearing.

Many Classical works employ a number of these topics, rather than just one. For example, Mozart’s Sonata No. 12 in F Major begins in singing style, followed by the learned style, hunting, storm and stress, minuet, and more. Haydn’s Sonata No. 62 in E-flat Major begins in the French overture style followed by singing style, brilliant style, learned style, hunting, and more.

Kay stated she has found it useful to have familiarity with these topics for helping pull her students from being overly focused on notes and fingerings instead of style and character.

10:30 Teaching Artistry: Do These 5 Things Now and Forever, by Veda Zuponcic

Veda Zuponcic gave a presentation about how we can develop artistry in the youngest student by consistently using five artistic building blocks. Veda has taught for ~50 years of teaching at the collegiate level and ~25 years at the pre-collegiate level. She accepts all types of students of all levels and abilities (no audition required for acceptance in her studio). She is a firm believer that stylistic comprehension and ability to deliver the style of a piece can be taught. Artistry is a process.

Artistry and technique: you can’t have one without the other. Here are the five artistic building blocks:

- Build fingers,

- Build a musical intellect,

- Build taste and style, and in the final analysis,

- Build artistry, and

- Develop confidence.

In a sense, Veda teaches her six-year-old beginners exactly the same way she teaches her college students. Of course, we must use different language and expectations in accordance with students’ ages, but the five points are still true.

Here are a few other notes I took from her session:

- Use

goodGREAT materials from the first lessons. Veda uses the best materials in order to get to Late Elementary/Early Intermediate levels (e.g., Anna Magdalena Bach) in one year. She uses primarily the Russian School of Piano Playing books, heavily supplementing to control the pacing (using Waxman’s Pageants, John Robert Poe’s Animal World, and many, many others). Veda encourages teachers to use the best materials they can find, especially for the early years. - Master every detail in the score — written or implied. The goal is to make the child musically literature to everything on the page.

- Work to a comfortable physical approach to the piano that allows a student to create a variety of sounds. This is different from technique. Emphasize physical freedom, using materials that are designed to avoid “positions” and constant contiguous writing.

- Build a big technique. Scales, arpeggios, inversions, with speed — contrary motion, etudes, etc.. You can’t play big literature without big technique.

- Provide opportunities for performance. At least a portion of the student’s repertoire should reach a high level of comfort and confidence. What’s the primary value of these performance opportunities? Preparation! Everybody needs deadlines, and children are no different.

Veda then showed excerpts from the Russian School of Piano Playing books, presenting the sequencing in those books. It begins with non-legato, a free arm, using only finger 3.

Next, she looked at a few examples of intermediate-level classical repertoire where the artistic building blocks still hold true and discussing how we can help students master the art of balance, sound production, fingering, voicing, form, and character. If we give our students these things at the beginning, they have a chance at continuing it to the end.

_________________________

For lunch, a large group of us walked over to a nearby Mexican restaurant called Maracas. So fun!

1:00pm Artistry–Can It Be Taught? by Hans Boepple

Hans began his presentation by sharing an analogy. Technique, musicianship, and artistry are like a three-story building. Technique can exist on its own. Musicianship relies on the support of technique, as a voice to existence. And artistry must have the support of both in order to support itself.

- Technique is the highly refined skills set that is required for the sound we want. It is the sound making. Required for dynamics, articulations, etc.

- Musicianship: balance (vertical), voicing, shaping (horizontal), rhythmic control (time control), pedaling, more. It’s the nuts and bolts of music making. Counting is an important skill.

- Something can be well executed, but lacking artistry. This is a performance that leaves you wondering: why are my emotions not stirred? Artistry is emotion and imagination. Technique and musicianship skills are not enough — they are to serve the music to project the core value of the music: its character, emotions. Artistry needs language to express itself, and the language of musical performance is musicianship.

And so, the question: Can artistry be taught? Technique and musicianship are skill-based. Artistry cannot be taught in the same way, because it is of a different nature. However, it can be brought to light. Most students are interested in being musicians, instead of keyboard operators.

Hans then discussed ways to build technique, musicianship, and finally, artistry in students.

Technique work is like athletes working only on mechanics to develop facility and prevent injury. Character pieces are wonderful for working on musicianship skills such as balance, dynamics, etc. and guiding students’ artistry development, much like creating a soundtrack for a movie. “Is this an indoor piece, or an outdoor piece? What is the weather like? What time of day is it? What is he/she wearing? A hat? How is she feeling? Why is she sad?” With a little leading, the student can create her own story. Then you can ask: “Can you play it that way?”

Dealing with this question many times over a year certainly helps build the imagination: “What does it feel like to you? So, how can we make it feel like that?” It’s asking students to invest themselves in the process and make it personal.

2:15pm Teaching Artistry Through Form, Phrasing and Dynamic Planning, by Theresa Bogard

To Theresa, artistry is learning how to make musical decisions yourself. Can artistry be taught? Yes and no. It’s not completely teachable, but you can cause a student to make it happen. But it’s definitely not the case that musicians are either “born with it” or not.

Theresa drew a distinction between being “unmusical” versus merely “inexperienced”. Our students are inexperienced. Becoming musically expressive is something that can be learned and must be taught.

What contributes to a less-than-satisfying performance by an inexperienced student? These are the issues Theresa discussed:

- Technical issues associated with tonal control, such as poor balance between the hands, weak voicing, and poor tone matching.

- Lack of external listening

- Lack of subtlety in interpretation of dynamics markings

- Problems in tempo flexibility

- Lack of understanding of phrase length and shaping (this is related to the previous issue)

Theresa believes it’s important to develop students’ independence — meaning, ability to make musical choices. Developing musical taste takes time, but it’s worthwhile.

3:30–4:30 p.m. Heather And Joy: The Beginnings Of Group Teaching, And Activities To Keep Students Engaged, by Heather Smith and Joy Morin

Next, I switched rooms to head over to the Recreational Music Making (RMM) track. Here, I listened to Heather Smith present about her recent forays into offering keyboard classes to groups of up to eight beginners and preparing them for the Royal Conservatory of Music (RCM) Preparatory A level exam by the end of the school year. It was neat to hear about and learn from her experience doing this!

Heather’s half hour session was followed by my half hour session, which was called “Activities to Keep Students Engaged.” In my presentation, I discussed what “engage” means (hint: it’s not only about holding someone’s attention; it’s also about inducing them to participate) and then described how I hold my monthly “Piano Parties”. Then, I described six games that I consider “go to” games for use during my Piano Parties.

The six games I shared about were (perhaps you already know these from here my blog!):

- Amazing Keyboard Race – Practices key names. Optional: include #s and bs.

- Recognizing Rhythm Patterns Aurally and Swat-A-Rhythm game

- Heartbeat Charts activity – Simplified rhythm dictation.

- Rhythm Dictation – Use cards to notate rhythms. Optional: race against another team!

- Grand Staff Pass – Practices note names. Mixed ages/levels okay!

- Ice Cream Interval Game – Practices interval recognition. Solo or group activity.

It was an honor to be invited to be part of the RMM track! If you’re interested, you may view and download the handout from my presentation here.

For dinner that evening, I joined up with three other teachers — Justin Krueger, Roberta Brooke, and my friend Amy Chaplin — for a meeting to discuss the panel discussion session we would be giving later during the conference (on Wednesday). We walked down to a lovely restaurant called Minuza, where I enjoyed smoked salmon bruschetta and a refreshing salad.

The official opening session and evening concert for the 2019 MTNA conference was held that evening at 7:30pm. I was happy to hear the opening remarks and welcome. Unfortunately, because I had pulled an all-nighter the night before and my body was still on Eastern time, I was too tired to stay up for the concert. And so, I missed out on hearing the Transcontinental Saxophone Quartet in favor of heading back to my host’s home to get some shut-eye!

Check out my notes from the Day 3.