Yesterday’s pre-conference sessions at 2015 National Conference on Keyboard Pedagogy were outstanding, and the sessions on the official first day of the conference were just as great! Here is a summary of some of the events.

8:00 Publisher Showcase by Sekwang Music Publishing Company – Smart 8: An Integrated Art Program that Develops Multiple Intelligence and Musicianship

First thing in the morning, I attended a publisher showcase by Korean publisher Sekwang Music Publishing Company. Lea Kang led us through a wonderful demonstration of the arts and movement activities of her new books called “Smart 8.” The book is completely unique from anything I’ve seen before. To be clear, it is not a piano method; rather, it is an integrated arts book that I think would be very fun and wonderful to use for offering group pre-piano or arts appreciation courses to young children. The beautiful book is filled with artwork to admire, think critically about, and experience through movement and music activities. The author enthusiastically led us through a series of the movement activities, some of them involving props such as scarves, ribbon wands, and hand-held music instruments.

[Note: So far, I haven’t been able to find where this book is available for order online. I’ll update this post with a link if I am successful in finding out that information.] The Smart 8 books can be ordered at SmartEight.net. In addition, you can watch a video of the entire NCKP session on YouTube here.

9:20 Keynote Address: Edwin E. Gordon – Beyond the Keyboard (read by Scott Price)

Dr. Edwin Gordon is an eminent music researcher and thinker whose work has hugely impacted music teachers all over the world. I was first exposed to Dr. Gordon’s work and what is known as Music Learning Theory (MLT) during my undergraduate studies at Hope College when he visited as a guest lecturer. I was excited about the opportunity to hear him speak again. Unfortunately, however, Dr. Gordon was recently admitted to hospice care with acute Leukemia. It was announced that Scott Price would read Dr. Gordon’s speech for us to hear.

Dr. Edwin Gordon is an eminent music researcher and thinker whose work has hugely impacted music teachers all over the world. I was first exposed to Dr. Gordon’s work and what is known as Music Learning Theory (MLT) during my undergraduate studies at Hope College when he visited as a guest lecturer. I was excited about the opportunity to hear him speak again. Unfortunately, however, Dr. Gordon was recently admitted to hospice care with acute Leukemia. It was announced that Scott Price would read Dr. Gordon’s speech for us to hear.

Dr. Gordon’s speech summarized and discussed certain aspects of the Music Learning Theory and encouraged us to make small changes in our teaching towards these perhaps radical ideas.

According to MLT, music (similar to language) consists of certain vocabularies:

- Listening vocabulary

- Singing and chanting – also involves movement

- “Audiating” and improvising

- Reading vocabulary

- Writing vocabulary

Piano study often begins at vocabulary number 4, which is reading. However, this can cause much frustration for the student who has not yet attained, for example, a listening vocabulary. Just as language has syntax, music has sound context. Just as with language we think we words, and we audiate music with patterns. Teach students music and then show them how it looks. Grammar should be taught AFTER a student can read and write a language with understanding.

Reading is not the pinnacle of music education. Reading is about extracting meaning. It can be an intrusion on music expression. Notation is more subjective than objective. We cannot put into notation all that we do when we make music.

Writing is a natural consequence of audiating and writing. Many students who begin with reading and illiterate when it comes to writing. But this does not happen when students learn to audiate as they read.

To summarize, Dr. Gordon’s speech encouraged us to remember that music education is the mind, not the piano. Be open to change that will improve our teaching, and try to implement those changes a little at a time. He encouraged us to learn about MLT further through reading his books (two mentioned were Learning Sequences in Music and Essential Preparation for Beginning Instrumental Music Instruction) and exploring Marilyn Lowe’s piano method that is based on MLT, called: Music Moves for Piano.

[I will add here that another great book for those new to MLT is Eric Bluestine’s The Ways Children Learn Music.]

Update: NCKP has posted Dr. Gordon’s entire written speech here.

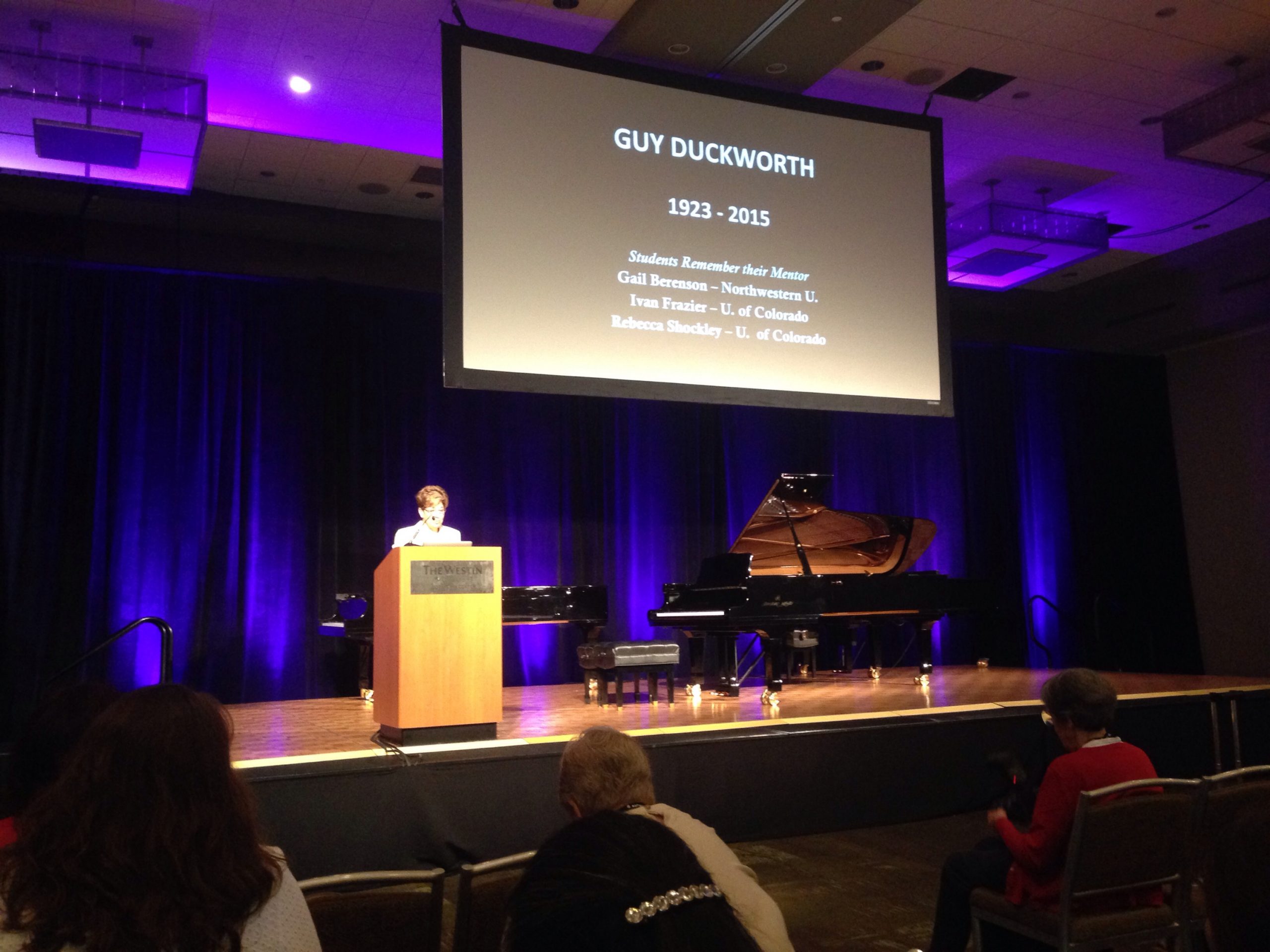

10:20 Celebrating the Legacies of Guy Duckworth and Louise Goss

The next session honored two pedagogues who passed away in 2015 and 2014 respectively: Guy Duckworth and Louise Goss.

Gail Berenson, Ivan Frazier, and Rebecca Schockley spoke about their experiences as college students of Guy Duckworth. Guy’s most important contribution to the field of piano pedagogy was perhaps his proponing of group private lessons. Rather than having one-on-one piano lessons, his college students stayed through each other’s lessons. And it was not just observation; Guy got everyone involved with providing feedback, playing ostinatos on the second piano along with the performer, dance-like Dalcroze Eurhythmics moves, etc. Guy was very interested in dance and health and fitness. He promoted an integrated technique using the whole body, before Dorothy Taubman and other technique approaches arose. Seeing Guy work was energizing and engaging. Guy never told students what to do. He asked questions or asked them to do things. Rebecca stated that under Guy, she learned how to tap into her emotional response to music. She explored her Music Mapping dissertation and later, her book with the same title, under Guy’s guidance and supervision.

Judith Jain spoke next about Louise Goss‘s legacy. Louise Goss was in important friend and partner to the pedagogue Frances Clark. Together, they founded the New School for Music Study (a music school in New Jersey that still thrives today and specializes in piano teacher training) and co-wrote important materials such as The Music Tree piano method. Today, the legacy of Frances Clark is furthered through the Frances Clark Center, a nonprofit whose work consists primarily of three divisions: The New School for Music Study as mentioned earlier, the National Conference on Keyboard Pedagogy (NCKP), and the fantastic Clavier Companion magazine.

During Judith’s dissertation work, Judith interviewed Louise Goss personally at her apartment. A few video clips from the interviews were shared during her presentation. The conversations allowed us to get a taste of Louise’s core beliefs about music and education. Education at its best is holistic: First we teach the student, then we teach the music, and last, the piano. All around the world, it is so often taught backwards. We tend to just teach students the music, instead of teaching through principles that will benefit the student in the long run as an independent musician and person. Piano pedagogy should be an outgrowth of education.

During Judith’s dissertation work, Judith interviewed Louise Goss personally at her apartment. A few video clips from the interviews were shared during her presentation. The conversations allowed us to get a taste of Louise’s core beliefs about music and education. Education at its best is holistic: First we teach the student, then we teach the music, and last, the piano. All around the world, it is so often taught backwards. We tend to just teach students the music, instead of teaching through principles that will benefit the student in the long run as an independent musician and person. Piano pedagogy should be an outgrowth of education.

11:15 Pamela Pike – Behind Closed Doors: What Our Pre-College Students Really Do During Practice and How We Can Empower Them

In her session, Pamela Pike shared her research project where she studied how piano students spend their practice time. She collected and observed practice videos of students of professional teachers from around the country and then interviewed the students and parents. The students in the clips thought they were using effective practice strategies, but the videos revealed the reality that the students mostly playing through pieces from beginning to end without truly solving mistakes and problem areas.

In her session, Pamela Pike shared her research project where she studied how piano students spend their practice time. She collected and observed practice videos of students of professional teachers from around the country and then interviewed the students and parents. The students in the clips thought they were using effective practice strategies, but the videos revealed the reality that the students mostly playing through pieces from beginning to end without truly solving mistakes and problem areas.

Most of the students did not appear to focus on musical goals, even when goals were notated on the assignment sheet. Rhythmic and fingering errors were rarely addressed. Practice sections were too large. The techniques that were used to solve problems did not match the actual problem. The students played with no or little dynamics and musicality (except for those dynamics and musicality that were developed during lesson time) and did not appear to listen carefully to their own sound.

The overall result of study revealed that most students maintain changes made during the previous lesson, but do not actually make a lot of progress on their own between lessons. In other words, there is a disconnect between what students take away and what they DO during the lesson. This is true despite the fact that the teachers who participated in the study were eminent teachers and the students were high-achieving students in music.

Pamela posed the big question that we must ask ourselves: Is what we are doing at the lesson both meaningful and related to home practice? Do we really teach our students how to practice? After all, the purpose of the piano lesson is to prepare for the next six days. Pamela made a variety suggestions for how we as teachers can help our students becomes good practicers. Here are just a few highlights:

- Students should not be told what to do. They need to learn to make their own conclusions. Telling does not help them get those problem skills or give them a sense of self-efficacy.

- A good goal is three things: specific, measurable, and attainable. These three things cause the student to be motivated towards the next goal. The goal should not merely be notated, but the student must spend lesson time showing us how they will practice it at home.

- Self-regulation is crucial, which involves listening and evaluating. Without it, students will not come back with effective change.

- Create a practice toolkit with the student. Encourage them to use game-like strategies to solve problems. Encourage them to record themselves and immediately listen. Consider integrating Nancy O’Breth’s three-page folder The Piano Student’s Guide to Effective Practicing into your teaching, or create your own handout with practice strategies.

- Be that the student attributes success to the practice strategy that was used.

12:15 Concert: John Perry Solo Recital

John Perry’s playing during the lunch hour was exquisite!

2:15 Diane Hidy and Elissa Milne – Distraction, Disorder, Dysfunction: 21st Century Child in the Piano Lesson

Educators, composers, and bloggers Diane Hidy and Elissa Milne gave an engaging session together about teaching the 21st century child. Our students have changed, and so have parents. Parents no longer think of piano study as something to do, but as something that will make their child smart. The so-called “Mozart Effect” and similar research has permeated popular culture.

Think of a time when your working memory has been exhausted. For example, trying to remember a long set of directions. This is how our students feel most of the time in the piano lesson. Often we think of errors (such as missing an F#) as reading errors. We label or circle it over and over. If we cannot get into the same category or sorting as the student, we cannot help them solve the problem. It might be a shape error, or an aural error.

We must remember that students do not see things that we automatically see, or sort, or categorize. We must teach students to see things, and we must be sure to correctly categorize errors for/with our students. Diane and Elissa discussed so many great examples, but here are a few:

- Visual Focus: Ask students to cover everything on the score with Post-It notes except for the chords on beat one. Play those, and then gradually build the piece back up. This enables visual focus. Covering can actually help us see what is there.

- Auditory Focus: It is all about playing with and changing the sound. After all, the piece sounds like this because it doesn’t sound like this. Music notation is really a confounding thing, because one cannot exactly notate the range of sounds (just think of articulation, for one!) that we can and should use during playing.

- Kinesthetic Focus: Music making is a bodily experience, which we sometimes forget. What is the experience of playing up into a black key? Use props that are tactile and fun to pull the student’s kinesthetic focus to the desire objective. For example, use animal erasers on the keyboard to show the shape of a D major pentascale.

Next, Diane and Elissa discussed the signs for knowing when to pull focus during a lesson. A yawn, wiggling on the bench, or not following instructions can be signs of cognitive overload or under-stimulation. These and other signs can tell us what is going on with the student. These behaviors at one time could have been interpreted as disrespect, but in today’s world, these are signs of students trying to be successful. The teacher has the responsibility to help the child save face and pull their visual, auditory, or kinesthetic focus as needed.

If you haven’t already, I highly recommend checking out both Diane’s and Elissa’s blogs (links above).

Later at the “Australian Music” booth in the exhibit hall, Elissa and Diane indulged me with a group photo.

Stay tunes for notes on Day 3 of NCKP 2015! Update: Click here for Day 3.

Joy, thanks so much for these posts on the NCKP. They are invaluable to those of us who could not make it. You’re doing a great job reporting on the sessions.

Thanks, Barbara! Glad to hear you are enjoying my notes!

Great Job! thank you so much for your posts about NCKP. I really enjoy reading them. I organize a event about piano pedagogy in Brazil (link above) and your posts inspire me. thanks!

Joy, thank you so much for sharing your fine notes with those of us who were unable to attend. I was wondering something about Dr. Gordon’s address. Considering the “listening vocabulary” before the “reading vocabulary”, what would you say that actually looks like in the piano lesson with a young beginner? Would it include teaching them songs by rote regularly along with their reading? Or strictly rote for a period of time before learning to read music? And if so, how long a period of time? I personally love teaching the Piano Safari rote songs, but I only teach a few in the beginning, and then I abandon them due to lack of time in a 30 min lesson. Perhaps my mindset is so conditioned to piano lessons=reading music, and yet I have benefitted so very much in learning to play without written sheet music myself, and using chord charts and lead sheets. Sorry this is so long, but this is a topic I often consider.

Hi Robyn! That is a tough question. Those who are interested in MLT have to each figure out for themselves how at a practical level to incorporate the theory into their teaching. I do recommend reading Eric Bluestine’s book for some ideas about this. My opinion is that to fully incorporate MLT, a great deal of aural music making should happen prior to and in accompanying with notation. But this aural experience isn’t just about entire rote pieces though; it is about learning to audiate and perform short rhythm and melodic patterns. I think this plays out as lots of clapbacks and call-and-response work!

Thanks for your insight, Joy.